The notion of the divine feminine is a recurring motif in American pop culture, playing with the assumptions people make when referring to God – often the deity described in the Bible – as “He.”

Whether it’s Alanis Morissette’s iconic portrayal of God in the 1999 comedy “Dogma” or Ariana Grande’s titular declaration in her 2018 track “God is a Woman,” the effect is the same: a mixture of irreverence and empowerment. It dovetails, moreover, with a ubiquitous political slogan: “The future is female.”

But in a historical moment when society is bitterly contesting ideas about gender, we’d note that these notions still rely on a simplistic binary.

As two scholars who study the entangled history of spirituality and gender, we often observe an especially fraught version of this dynamic playing out among “spiritual but not religious” practitioners, often called spiritual seekers. To many such people, the divine feminine represents an escape from oppressive gender norms, and yet many stumble in trying to reconcile the idea with the embodied realities of biological sex.

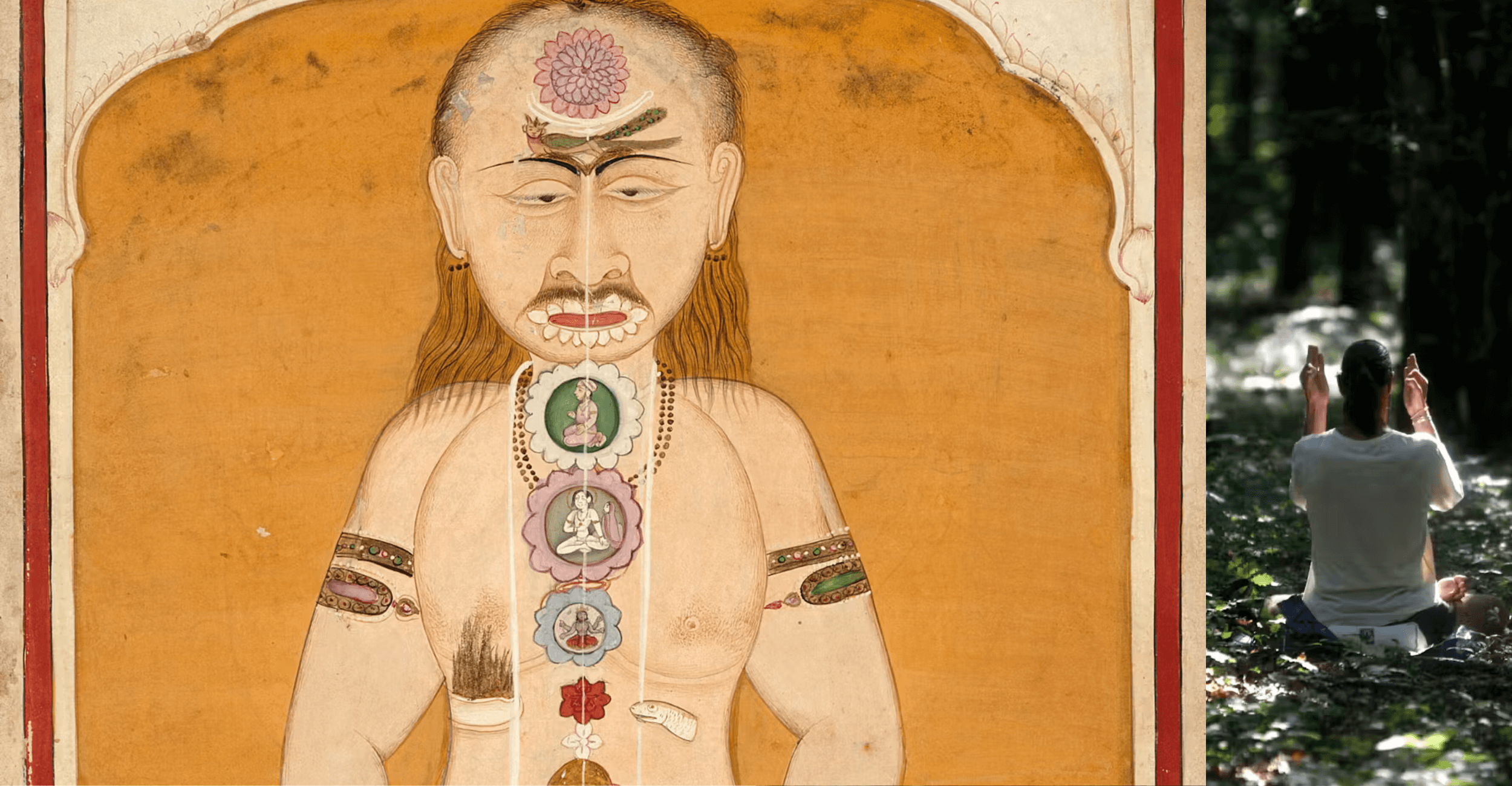

An approach that escapes this dilemma is the centuries-old Kundalini tradition, which paints a model of the divine feminine beyond gender altogether